Dance Styles

|

We occasionally indulge in swing and latin dances that are performed

in one place on the dance floor, but our basic passion is for dances

that travel while spinning and whirling about until we are giddy.

Here are the dances that satisfy this criteria, that have a well-known

historical context:

|

Traveling Dances

|

Traveling Dances

|

bpm

|

Description

|

|---|---|---|

| Blues | 50+ | A sensual one step, a two step (Waltz etc calls it a blues trot) and a waltz (when in 3/4 time). |

| Turning waltz | 120 to 180 | Basic waltz, before the 20th century, with a long history and endless variations. |

| Cajun waltz | 120 | Distinctive syncopated waltz from Louisiana. |

| Vintage waltz | all speeds | 19th century waltz variations, redowa-polka, mazurka, Boston, ragtime waltzes. |

| Cross step waltz | 110-130 | Cross-step waltz is a swooping, playful step for slower waltzes. |

| Viennese waltz | 160-180 | The hyperspeed ballroom waltz. |

| Tango vals | 180+ | The 3/4 time version of the Argentine Tango. Steps per beat becoming something of a vague issue. |

| One step | In 4/4 time with a step per beat; the basic traveling step that became a huge national craze in the early 20th century. Easy, fun and expressive. | |

| Foxtrot | In 4/4 time with a syncopation on one beat of the measure; there are more variations to the foxtrot than the studios teach. | |

| Polka | In 2/4 time; as in the waltz, two musical measures to a dance phrase; fast and cheerful. |

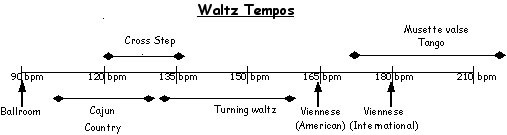

We define the waltz rather broadly: it includes any dance in Western culture that is in 3/4 time, travels around a dance floor and has a tendency to turn. There is a continuity within varieties of what we call waltz and that continuity is linked to the tempo of the music. The waltz is all about momentum. The dance becomes what the momentum of the music will allow.

The basic pattern our culture perceives as a waltz is a turning pattern, where partners face each other in closed ballroom position. They keep that position as they move around the dance floor in a revolving embrace allowing the tempo of music to give the necessary centrifugal momentum for both partners to move smoothly as one unit.

The ideal tempo for this basic pattern is in the 130 to 155 bpm range. A comfortable tempo that is slow enough that the feeling of the music can be expressed in a variety of ways. The couple can leave the embrace, do other variations, and then come back smoothly to the revolving embrace. The upper end of this range was the tempo of the waltzes during the great age of the waltz in the 1800's when it scandalized Europe with it's close embrace, and breathless speed. (This according to dance historian Richard Powers) This is also the range that is ignored by what is presently codified as ballroom waltzes.

As the tempo gets faster, its gets more difficult to leave the embrace and come back smoothly. This tempo demands that the turning, if it is to be sustained, be the main focus of the dance. The ballroom Viennese waltz that ranges from 165 to 180 bpm was developed for this tempo. There are also other possibilities.

Beyond 180 bpm, the waltz becomes a kind of syncopated one step in the tango waltz, the hesitation waltz, and other waltzes that have been developed over the years that allow us to omit stepping on every beat.

At the other end of the bpm spectrum are slow waltzes (90 to 100 bpm). At this speed there is not enough momentum developed to dance in the revolving embrace pattern. The modern ballroom waltz, with its long steps and sense of drama, was developed to make up for this lack of momentum. This waltz is taught in most studios very well and is not taught by Waltz Eclectic.

Increasing the speed a little to the 100 to 125 bpm the cross step waltz with its equally balanced surge on beat one and four by the lead and follow, respectively, and its smooth and flowing steps, offers a transition between the long steps and angular patterns of the ballroom waltz and circular rotations of the turning waltz. It has the playful nature of the one-step combined with the blissful feeling of the revolving embrace.

Within this musical spectrum, the waltz visits a wide range of cultures and styles. It virtually takes you around the world in musical gesture and nuance.